What is the Lemminkäinen Hoard?

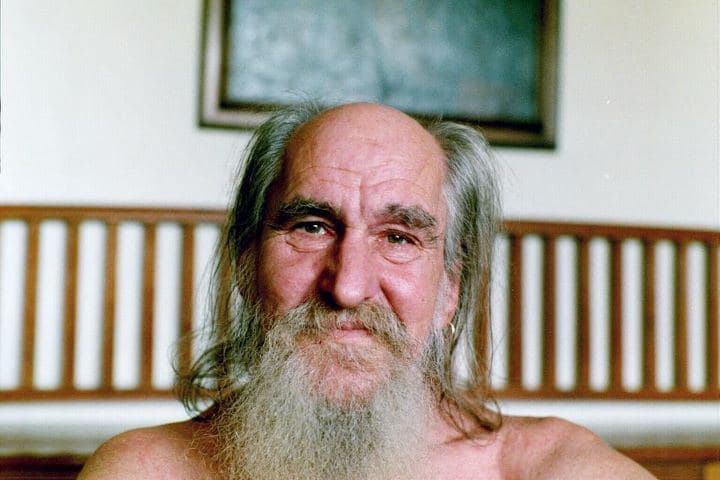

The alleged existence of the Lemminkäinen Hoard first emerged in 1984 when Ior Bock claimed that his family – one of the oldest in Scandinavia – were direct descendants of Lemminkäinen, a figure from Finnish pagan mythology.

Hunting for treasure and the truth!

The Lemminkäinen Hoard

Bock claimed that tens of thousands of jewels, ancient artefacts, and life-size gold statues of Lemminkäinen himself had been stashed within the labyrinthine Sibbosberg cave system close to the coastal resort of Gumbostrand, 20 miles east of Finland’s capital, Helsinki.

Bock alleged the cave, situated on his sprawling ancestral estate, was home to the fabled Lemminkäinen Temple where the collected treasures from countless generations of ancient Finnish pagans had been stored.

According to Bock, the temple entrance was sealed up with huge stone slabs in the 10th-Century to protect the treasures within from invading Swedish and Swiss armies.

His aged family line—the Boxström—had been keepers of the secret, and guardians of the cave, since then.

The story captured the imagination of many worldwide who flocked to the site in search of truth, gold and glory, including members of The Temple Twelve, who joined forces with Ior Bock to become the site’s first and only permanent, self-funded excavation team.

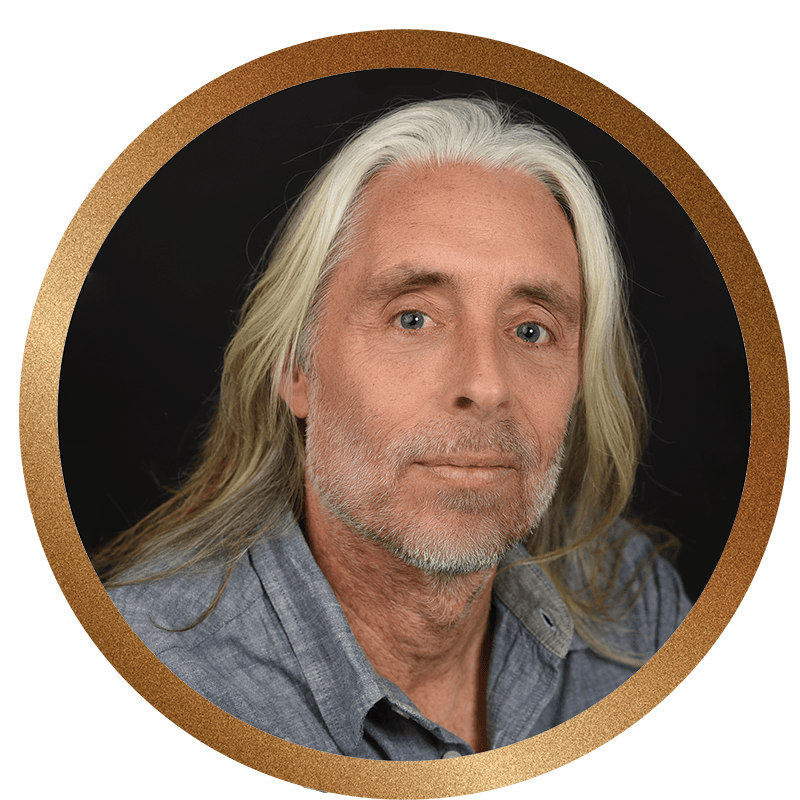

Carl Borgen, a friend of Bock and the world’s leading authority on the hoard, has been following ongoing excavations at the site for more than 30 years.

Carl’s book, Temporarily Insane, chronicles the Bock Saga and follows the fanatics—or ‘Bockists’—who have devoted their lives to finding its supposed treasure.

We’re entering the end game and, if we win, the treasures to be found there will be unimaginable…

Carl Borgen

Author of Temporarily Insane

Hero of the Kalevala

Who is Lemminkäinen?

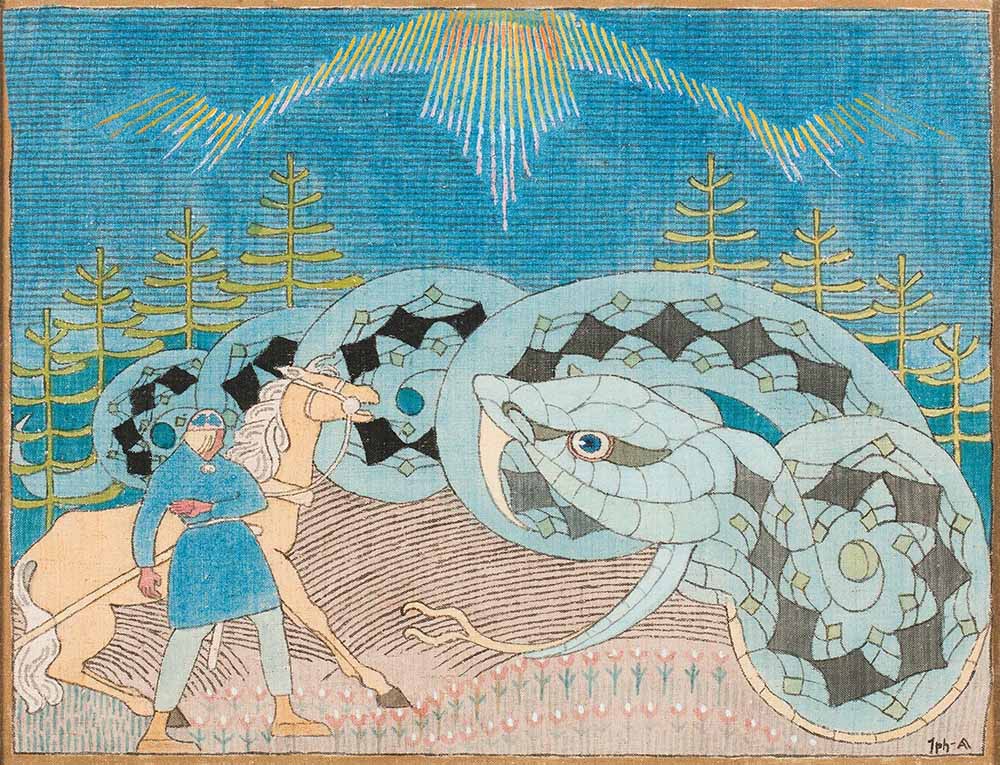

A prominent figure in Finnish mythology, Lemminkäinen is one of the heroes of the Kalevala, a 19th-century work of epic poetry compiled from Finnish oral mythology and folklore.

Often depicted as a handsome, red-haired hero and a warrior, Lemminkäinen is sometimes also portrayed as a ‘frivolous’ and arrogant womaniser.

Lemminkäinen’s main appearance in folk poems is the story Lemminkäisen virsi (Song of Lemminkäinen), but he has also been attached to other stories, such as Hiiden hirven hiihdäntä (Hunting the moose of Hiisi on skis). The Kalevala combined multiple different stories to create its Lemminkäinen character.

In many versions of the tales, Lemminkäinen is killed and dismembered. The method of his killing varies with the tales – in some he’s shot by an arrow – in others stabbed by a hollow reed, but in each version it’s always by “the one weapon that could kill him”.

His dismembered body is then cast into Tuoni, the River of Death in Tuonela, the Underworld.

Lemminkäinen’s mother, upon learning of his death, descends to Tuonela and uses a copper rake to retrieve his body parts from the River of Death. She “re-knits” his body, using magical honey to restore his life.

Scholars have noted the similarity of this story to the ancient Egyptian myth of Osiris, who was dismembered and resurrected, as well as to tale of the Norse god Balder who, immune from harm, was also killed by the only thing he was vulnerable to (in his case, mistletoe).

The poem is also thought to contain influences from the Russian bylina Vavilo i skomorokhi, a poem through which it is believed motifs from the Osiris myth were conveyed from Byzantium to northern Europe.

It’s assumed, therefore, that the story of Lemminkäinen is a composite of numerous myths and religions from around the globe.

However, perhaps the Bock Saga, which tells of the Aser traveling across the world to teach humanity following the end of the Paradise Time, has an element of truth after all. Suppose it was the original source of these similar world myths and not the other way around – who can say? Maybe the answer to this is another treasure to be found in the Lemminkäinen Temple…

Thus became a mighty hero,

In his veins the blood of ages,

Read erect and form commanding,

Growth of mind and body perfect

But alas! he had his failings,

Bad indeed his heart and morals,

Roaming in unworthy places,

Staying days and nights in sequences

At the homes of merry maidens,

At the dances of the virgins,

With the maids of braided tresses.